The 20th Century was a period of unprecedented technological advancement in almost every field. Communication in particular was revolutionized during that time, and each breakthrough would contribute in its own way to today's era of near-instantaneous distribution of information.

The first telephone exchange in North America became operational in 1878. But like the telegraph before it, telephones required an infrastructure of physical lines to work, and that limited their use to already developed urban areas. The first “long-distance” call spanned a whole six miles. It would take decades for telephones to become commonplace. Meanwhile another invention was on the horizon that would fill in some of the gaps. Radio was invented right at the turn of the century. Since radios broadcast over airwaves, they didn't need physical lines to operate, and this made them useful in areas that weren't yet well-developed and for shipboard communication. It also soon became a medium for popular entertainment, and a source for news. As the technology progressed, receiving units became small enough to be installed in cars, while two-way radios found their way into cabs, police cars, and trucking companies. They also became an essential tool for the battlefield tactics that were shaped by concurrent advances in mobility.

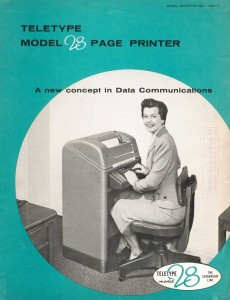

News agencies owe a great deal of their success in the 20th Century to yet another invention: the teletype machine. An evolution of the stock ticker, which appeared around 1870, the teletype machine allowed the user to send typed messages over a network of simple wires. To this day, we call companies such as The Associated Press and Reuters “wire services,” a name which stems from their use of the teletype. Teletypes were faster than sending messages through telegraphs, and one machine could send messages to several other machines at once. The receiving teletype would print the message out on paper automatically at around 60 words per minute.

The teletype was an early ancestor of the personal computer, and the network of connected teletypes foreshadowed the way in which computers would soon be connected to each other. There was nothing personal about the first computers. They were huge, vastly expensive machines developed to perform massive calculations for military purposes, notably the invention of the hydrogen bomb. In the post-war years, business found computers useful as well, and began to adopt them. By the late '60s, people in the field began thinking about ways to make computers more accessible to the consumer market. It would take until the late '70s for the personal computer to hit the market, but once they did they made a big splash, and they soon became powerful enough that business were replacing their mainframe-and-terminal setups with individual PCs.

Right around the time the computer industry was looking into personal computing, the Department of Defense was looking into ways to connect individual computers in a manner similar to the networks employed by teletypes. The result, ARPANET, would later be recognized as the starting point for the Internet era.

All of these technologies are interconnected, and have built upon each other. Today, we have smartphones. Part telephone, part radio, part personal computer connected to the Internet, they offer the user a variety of communication options in a device that fits in one's hip pocket. With this kind of access to communication, it's no wonder people are sending fewer letters than before. But interestingly, consumers do favor the mail as a medium for certain kinds of messages, such as advertising. Direct mail is favored by a significant margin over telemarketing and unsolicited e-mail. The challenge today's Postal Service faces is to find a way to make use of their strengths to cope with volume lost to other media.