The first postage stamps, introduced in Great Britain in 1840, revolutionized postal delivery. The United States Postal Service introduced its own stamps in 1847, and made them the only acceptable form of postage payment eight years later. Stamps allowed for postage to be prepaid by the sender. Before stamps, postage was usually paid by the recipient. This caused a few problems.

Most obviously, if a letter was undeliverable, no postage could be collected. Yet all the work had already been done to get the letter to its intended destination. Even if the letter found its recipient, he could refuse payment. Sure, he wouldn't get the correspondence, but the postal service was still out whatever it cost to make the attempt.

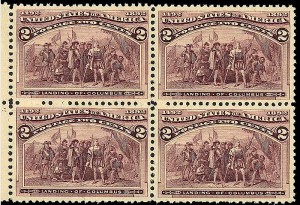

The first U.S. stamps came in 5- and 10-cent denominations, and featured portraits of Ben Franklin and George Washington respectively. The 5-cent rate was for letters of less than 1 oz. weight and traveling fewer than 300 miles. Ten-cent stamps were for heavier letters, or ones that had to travel farther. The improvement in efficiency was so great that in 1851, the Postal Service reduced their rates. With better, less expensive service came a marked increase in the popularity of sending letters. 1857 saw the introduction of pre-perforated sheets of stamps, making it even more convenient to use the mail.

The Civil War complicated matters of postage, with Confederate post offices sending their U.S.-issued stamps back to Washington DC. The USPS issued new stamps during the war years, and would no longer accept pre-war stamps, although they would usually exchange old stamps for current ones. Mail exploded in popularity once the war was underway, beginning the popular tradition of letters traveling back and forth between the troops and their loved ones back at home. All thanks to a simple piece of paper with some printing on the front, and a bit of adhesive on the back.